The importance of knowledge and knowledge management have been rising noticeably in the last decades: firms and organisations value more and more intangible resources and intellectual capital, and more and more competitive advantage is due to the ability of a given company to gain critical insights on the market, as investors well know.

According to NYU Stern Professor Baruch Lev, intellectual capital has killed financial reports. For instance, Uber raised $90 million after reporting $79 million losses, LinkedIn was paid $26 billion from Microsoft in 2016 despite frequent losses, and Whatsapp was bought for $19 billion from Facebook in 2014, without generating any revenue.

The reason behind lies in balance sheets and income statement: in the current digital economy, intangible investments have surpassed plant, property and equipment as the main mean of capital creation for many US companies. Income statements are believed to be responsible for 2.4% of stock returns only (Govindarajan, Rajopal, Srivastava. 2018). Another fallacy of standard financial accounting is that it misses the network effects that platforms such as Facebook and Google have generated.

Source: Ocean TOMO, LCC

Behind these dynamics, there are strong assumptions.

First of all, financial capital is assumed to be endless. Digital companies consider software engineers and data scientist the most valuable source of value, while financial capital will always be raisable with a round of investment.

In the second place, risk gas a new definition: knowledge companies enjoy litter like projects. The mindset is the one of continuously looking for the breakthrough innovation, and traditional cash flow analysis is not ready.

As a consequence, investors are attracted by ideas and forecasted earnings. Investors are also having a bigger and bigger role: companies are establishing venture capital branches to innovate.

Lastly, while financial reporting is following a process of worldwide standardisation around IFRS and GAAP Principles, financial analysts will have to rely on original and nonstandard metrics to capture knowledge company’s value (Govindarajan, Rajopal, Srivastava. 2018).

For sure, there is a strong influence of a topic mentioned before: Big Data. La Torre, Botes, Dumay, Rea, Odendaal (2018) have tried to describe the implications of Big Data for intellectual capital accounting in order to improve the understanding regarding the future of “accounting”. Big Data represents a new intellectual capital asset, and its value is determined bu data quality, security, users’ interaction, data visualisation and privacy issues. Big data value lies in the organisation’s capability to exploit the value of data possessed, i.e., the ability to perform big data analytics and data visualisation.

Definition and Taxonomy

It may be useful, before going deep in the knowledge management literature, to have firmly in mind what is meant with the word “knowledge”. Finding a definition is not an easy task, being knowledge a highly abstract concept, but it may help to use the typical approach of placing knowledge in a pyramid of adjacent terms: data, information and wisdom.

Source: Growth of multi-authored journal articles in economics | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal. (2020). Retrieved 19 September 2020, from https://voxeu.org/article/growth-multi-authored-journal-articles-economics

At first, data can be defined as facts and figures which relay something specific, but which are not organised in any way. Data becomes information once it is organised, structured, categorised, calculate or condensed: providing a schema to a particular fact help convey the first layer of context. Once data is organised in information, the acts of contextualisation, synthesis and comparison let information turn into viable knowledge. On top of that, the mastery of a chunk of knowledge can be called wisdom (Davenport, Prusack. 2000). The following example may be useful to clarify the concept.

| Data | Red, 192.234.235.245.678 |

| Information | South facing traffic light on the corner of Pitt and George Streets has turned red |

| Knowledge | The traffic light I am driving toward has turned red |

| Wisdom | I better stop the car |

If defining knowledge is not an easy task, finding a common framework seems a quite more demanding job: it still lacks a comprehensive and generally accepted framework despite the existence of 56 different proposals. The possible reason behind that is the lack of consistency with system thinking: the frameworks are not addressing the notion of double-loop learning and just prescriptive, while there is not a definition of what is a knowledge management framework and the structures used are very heterogeneous (Rubinstein-Montano, B., Leibowitz, J., Buchwalter, J., McCaw, D., Newman, B., Rebeck, K., & Team, T. K. M. M. 2001).

An Oriental Approach

Perhaps the main contributor of this thesis research is Ikujiro Nonaka, inspired by Japanese philosophy, which at the end of the second millennium proposed robust theories regarding the essence of knowledge in knowledge creation theory.

Everything starts with “ba”. Ba is a shared space that enables knowledge creation. It transcends the concept of the platform: it is a shared space, both mental, virtual and physical. The key concept is that once two people join a shared space (ba), they can learn from each other experience, and their experience becomes new information by letting ba apart and being communicated. Ba can be thought of as a place of knowledge sharing like project teams, working groups, informal circles, email groups, temporary meetings etcetera. As a consequence, joining a ba means to get involved in one’s perspective and transcend it, in order to let rationality and intuition mingle to form creativity.

As mentioned before, there are two kinds of knowledge: explicit and tacit one. The first one can be expressed in written forms (numbers, words, data, scientific formulae, manuals, et cetera), while tacit knowledge is often called sticky: it is highly personal, it is impossible to write down entirely or teach straightly.

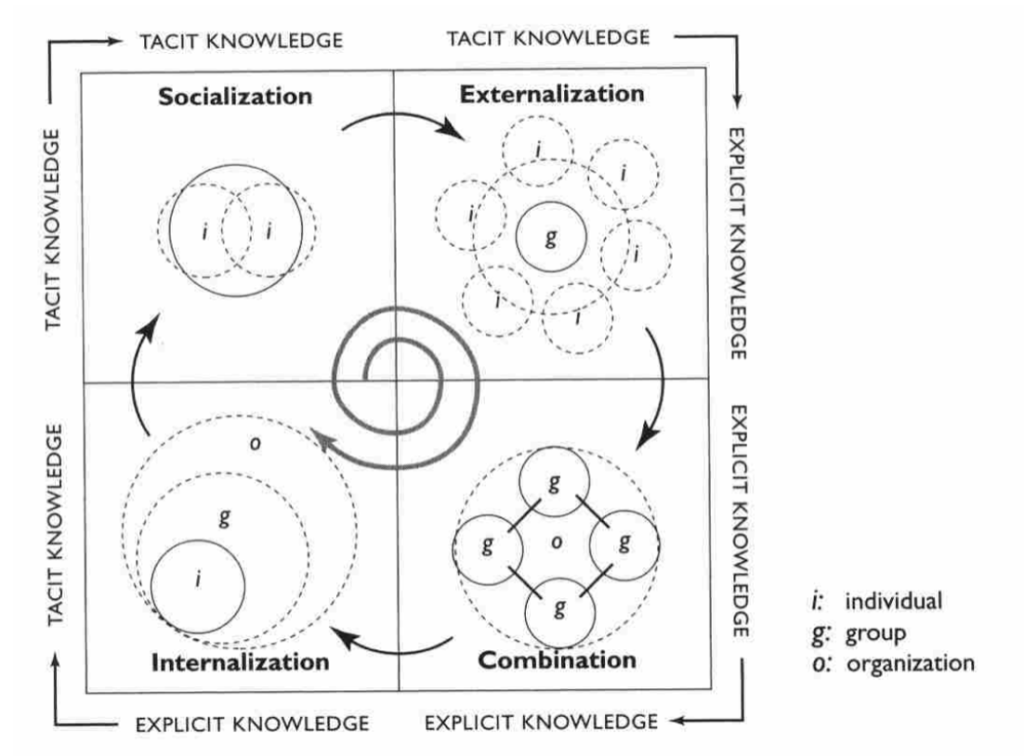

An external reader may miss some pragmatism and ask then how this ba is supposed to generate new patents and products. According to Nonaka, knowledge creation is a process, in which there is a continuous interaction between explicit and tacit knowledge that leads to a virtuous cycle of wisdom generation. In particular, there are four distinct moments of knowledge creation, that can be appreciated in the figure below.

Source: Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). The concept of “Ba”: Building a foundation for knowledge creation. California management review, 40(3), 40-54.

At first, socialisation is the moment in which two individuals shares tacit knowledge and can be both a conversation or tacit joint activities. Empathy is a critical ingredient for knowledge sharing. In practice, socialisation happens, for example, during dialogues among colleagues or suppliers and customers. The act of sharing tacit knowledge is a way of creating the ba, the common ground.

In the second place, externalisation is the moment in which tacit knowledge is translated into a written form. Of course, explaining to a kid how to ride a bike would not make him a hundred per cent proficient in bike riding, but it is part of the process.

Thirdly, the combination is the moment in which knowledge is made available because the organisation look for new solutions for spreading and make more usable the knowledge generated.

At last, knowledge is internalised in everyday practice thanks to training, exercises, learning by doing, et cetera.

The Knowledge Economy

The idea that knowledge is created in organisations’ space is also shared in Western literature: according to R. M. Grant (1996), firms are the place where specialist knowledge is integrated from individuals to create goods and services.

Which are the management practices that let coordination and cooperation be achieved? According to Bradley (1997), even though many firms were not ready to manage knowledge when his research was written, he recognised that the essential points for managing knowledge were creating structures, measuring its impact and making sure that intellectual capital was “decanted” in all the angles of the organisation.

Other factors that influence knowledge sharing are top management support, knowledge self-efficacy and the enjoyment of helping others. That may suggest that individuals tend to be willing to donate and collect knowledge to enhance the capability of the firm to innovate (Lin, 2007). In the image below, a model is proposed, with the strength of the different causes and effects. The model hypotheses that individual factors, organisational factors and technology factors influence the knowledge exchange capability of the firm, which turns into innovation output.

Knowledge and Competition

Knowledge management has some crucial implications for competition dynamics too: A. Carneiro prosed a conceptual model, having as a focus the relationship between knowledge management, innovation and competition. As it is possible to observe in the figure below, the individual, both at a personal and professional level, is the primary factor to generate knowledge, that is key in strategic decisions. It is thanks to the strategic decision that any firm can develop market knowledge and competitor knowledge, that brings compelling market innovation and good competitor understanding.

Source: Carneiro, A. (2000). How does knowledge management influence innovation and competitiveness?. Journal of knowledge management.

Moreover, it is important to highlight the role of open innovation, i.e., a model of innovation generation that involves external sources: management impacts knowledge sharing practice, that in turns influence open innovation and influence organisational performance (Singh, S. K., Gupta, S., Busso, D., & Kamboj, S. 2019).

J. M. Bloodgood (2019) adds a deeper level of analysis suggesting that the effect on competitiveness is not always positive and equal. However, it depends on different dimensions presented in the image below. Knowledge can be acquired internally or externally and can be acquired from competitors or not. These factors influence the degree of influence on firm knowledge, product and processes. Moreover, he proposes also that knowledge can have a different level of distinctiveness (stickiness, imitability) and criticality (usefulness), the impact on competitive advantage can vary.

The publications cited in the article can be found here.

Leave a Reply