Continuing from part 1

The Second Piece of Evidence

An external audience may suggest that the previous research is outdated, especially considering that innovation per se is a complex and dynamic process, so it may be helpful to go through another piece of literature briefly.

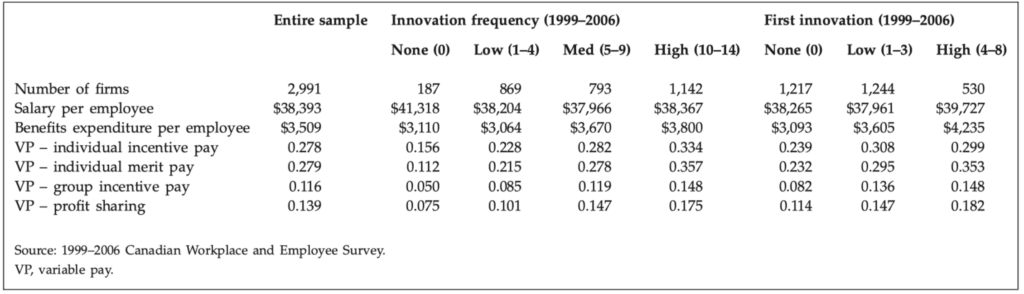

In 2014 Bruce Curran and Scott Walsworth took seven years of data representing Canadian private sector innovation performances to estimate the different effects of the significant components of components. Coherently with the previous results, the findings suggest that fixed pay and individual performance compensation do not affect innovation while variable and indirect payment, such as employee benefits, positively affect.

In the study, the independent variables examined are fixed pay (salary), variable pay rewarding individual performance, uneven pay rewarding group performance and indirect compensation. In contrast, the dependent variable examined is the frequency of innovation (Innovation Frequency Scale) and the significance of the innovations (First Innovation Scale). The first range from 1 to 14, the second one from 0 to 8.

The data were from the Canadian Workplace and Employee Survey (WES). The workplace level of measurement is the workplace one, which is more desegregated than the firm’s one. The same workplaces were re-surveyed every year from 1999 up to and including 2006 by computer-aided telephone interviews.

In the table below, it is possible to check the data collection results and grasp some insights: counter-intuitively, the most paid employees are also the ones less likely to produce frequent innovation. At the same time, benefits expenditure increases both with the innovation frequency variable and the first innovation.

Considering the probability of having an incentive pay in plan (marked as “VP”), the average workplace reported a 27.8 percent likelihood of having an individual incentive pay plan in place. Higher frequencies of variable pay are correlated with more increased innovation outputs: taking the personal incentive pay line, workplaces reporting no innovations were less likely to have such a plan (15.6 percent), and workplaces with high-innovation frequency were more likely (33.4 percent), and the same happens in the following three lines.

Once more, specific forms of incentive pays are highly correlated with more excellent innovation performances.

The Antecedents of Creativity

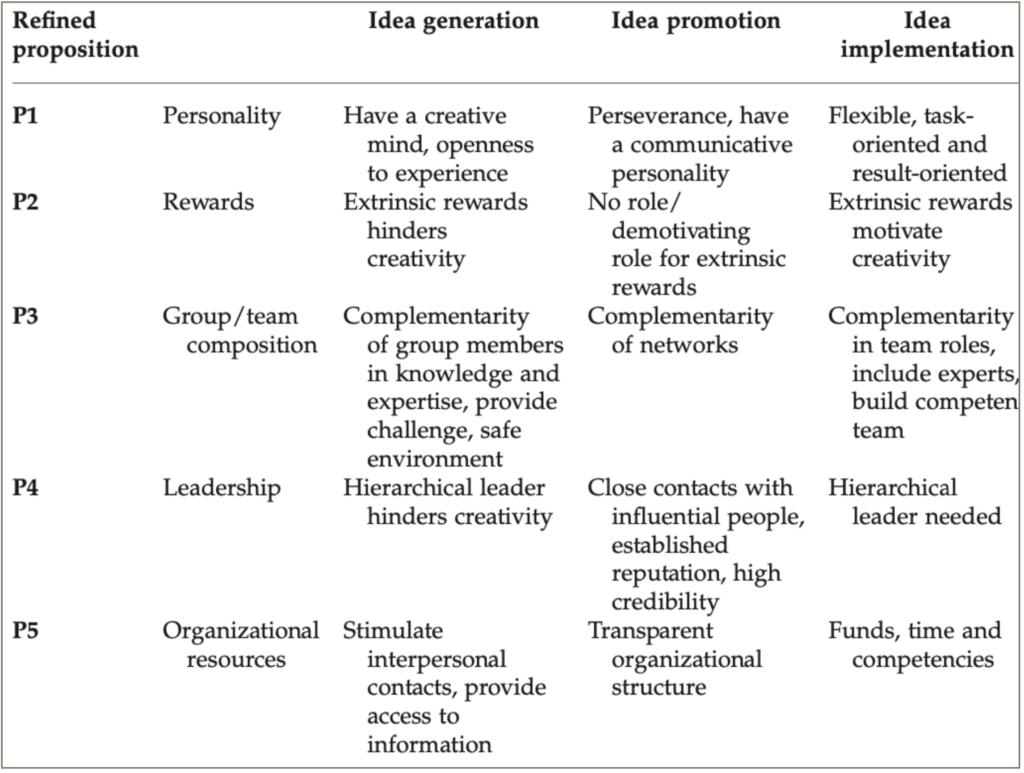

Until now, innovation has been considered an activity. What if instead it is seen as a multi-staged process? Marjolein C.J. Caniëls, Katleen De Stobbeleir and Inge De Clippeleer emphasised this topic by identifying the role of five “antecedents” of organisational creativity played during the different stages of the creative process: personality, rewards, the part of co-workers, leadership and corporate resources. According to the researchers, the innovation process is split into idea generation, promotion and implementation, and without the assumption is that without the right incentives in the right moments, the flow ceases.

Data are collected through a 36 semi-open question interview from knowledge workers and artists of diverse industries because they are the ones who have to come up every day with solutions in non-routine situations more frequently.

Diving into the table, the rewards line gives exciting answers. Idea generation seems to be inhibited by external rewards as if the accommodation of external requests limits the employees’ independence, which would benefit more from independent creative thinking. The logic is similar for idea promotion: extrinsic motivation seems to inhibit the process, while intrinsic motivation spreads the idea around the organisation. Employees need to passionately and genuinely believe in their vision to promote it. On the other hand, external rewards facilitated the implementation of ideas: the interviewed stated that idea implementation is the most crucial and most challenging part, and the prospect of being rewarded was seen as an essential motivator to keep pushing towards the full implementation taking care of all details.

Therefore, the whole innovation process would stop after the idea generation if it wasn’t for external rewards, making it impossible for the company to launch the idea on the market and cover costs successfully. Implementation is the right step of the path in which you should invest to avoid sunk costs, and monetary incentives are the best way to keep innovation flowing when they are paid at the right time.

In the end, even if the study has been conducted among a restricted number of participants, its results may help in explaining the heterogenous evidence from the previous studies.

Incentives and Environment

Not surprisingly, the literature against the research hypothesis is relatively consistent, and it mainly rotates around the view of the organisation as an environment in which different factors influence employees’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

As the first example of that, Amabile’s model shows how the working environment influences employees motivation and individual creativity or innovative propensity: innovation is seen as the intersection of creativity, intrinsic task motivation and creative skills, that are itself a result of different environmental factors, such as organisation’s resources, organisational motivation and management practice. The proper management of the corporate environment is the bridge between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation and innovation propensity.

Moreover, when millennials are taken into account, the efforts to provide an innovative culture with non-traditional incentives could pay off big-time: new research shows millennials favour creative cultures. The opportunity to work on innovation initiatives can be an incentive in itself. Five essential elements constitute the ability of the management to stimulate creativity or innovative propensity within an organisation: culture, climate, organisational structure and systems, leadership style, and knowledge/expertise, pretty consistently with the Amabile’s Model.

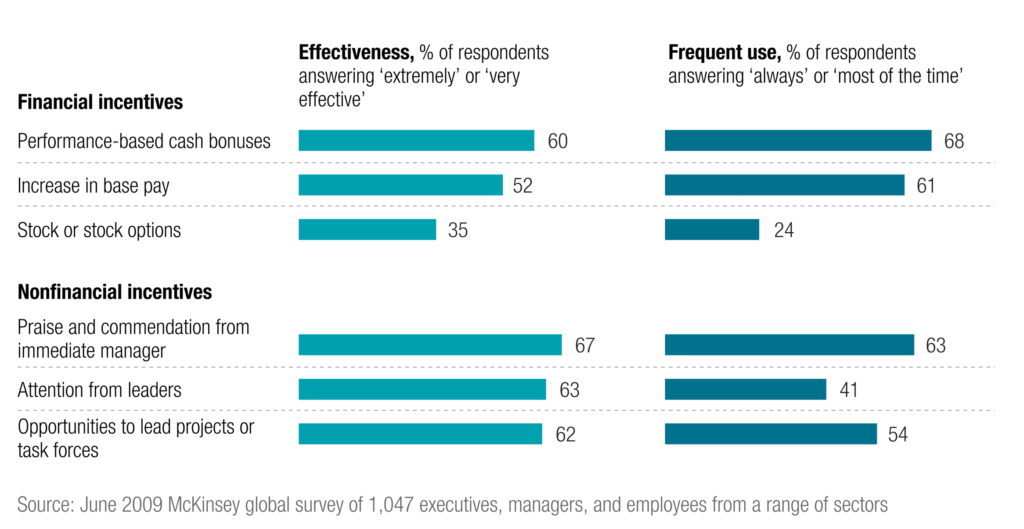

A 10 years old McKinsey Survey had a similar conclusion from a sample of responses from 1,047 executives, managers, and employees worldwide. More than a quarter of the respondents were corporate directors or CEOs, or other C-level executives. The answers are presented below.

The most popular incentive on the survey was praise from the boss, the second was attention from leaders, and the least popular was stock or stock options. All three of the non-financial incentives were more popular than the leading financial incentive. The survey’s top three non-financial motivators play critical roles in making employees feel that their companies value them, take their well-being seriously, and strive to create opportunities for career growth. These themes constantly recur in most studies on ways to motivate and engage employees. Non-financial incentives were rated as more powerful motivators than financial incentives.

How to deal with those arguments? We should mention few points:

First of all, is intrinsic motivation entirely intrinsic? Slightly repeating what has been written previously, Fontana, D’Alise, & Marzano have run three company analyses. Two of the three use variable monetary incentive since they are preferred to a fixed financial incentive. The findings suggest that extrinsic incentives and economic reward are crucial for innovation and several other factors. Those are: a sense of belonging to the organisation, the pride of working in the organisation, responsibility, autonomy, formal and informal acknowledgement, and, first of all, the actual implementation of the idea proposed by the innovator, are considered the most incisive stimulus to individual motivation to be creative, the main factors that positively affect the propensity to innovate. What is essential is that incentives provision and payment can boost all these factors that constitute the intrinsic motivation: a free day for an employee is still a monetary incentive because it is still a cost of paid holiday that the organisation has to sustain. Using two quotes to summarise the concept, “An innovative firm requires a high degree of affective commitment from its employees, and it may offer benefits as a means of recognising and facilitating this commitment” (Martocchio, 2004; Milkovich et al., 2010).

In the second place, are employees aware of their needs? You may notice that it is harder to find data about the correlation between non-monetary incentives and innovation without passing by interviews. Someone may guess that people are not fully aware of their own inner Maslow’s pyramid. They perhaps tend to neglect the lower stages of the pyramid and give the living condition that their innovation-related job can contribute to them.

Conclusion

All in all, while it is easy to conclude that incentive pay is a fundamental motivator for innovation propensity, it is harder to figure that it is the best one. While there are strong theoretical background and solid evidence on cash’s positive effect on innovation, there is also good (but more subjective and “human”) evidence that other non-financial incentives play an important role. A big issue is statistically disentangling the different effects of the motivation factors in the workplace. For instance, it would be almost impossible to study innovation employees persistently unpaid and only non-economically incentivised for long periods, and in general, salary is at the basis of job conditions.

From my perspective, having to select future research would be nice to broaden the problem into gamification theory. Gamification is the application of game-design elements and game principles in non-game contexts. It commonly employs game design elements to improve user (or employee, in this case) commitment, using scoring systems, badges or other visual representations of achievement, leaderboards, performance indicators, rewarding systems, milestones creation, storytelling elements, internal competition, et cetera.

Is the innovation challenge correctly incentivised among firms? Are HR departments aware of how to make everyday problem solving compelling? Do employees want to play the game in which the company exists? Are the tools provided enough to beat the upcoming levels? Are monetary incentives the best way to create the "innovation game"?

I wanna thank Chiara and Riccardo, that run the research with me during university.

Cited in this article:

- Innovation Ranking 2019. Are you among the most innovative companies in the world? https:// www.patentsight.com/innovationranking

- Abraham Maslow (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review. 1943. Josh Lerner and Julie Wulf (2007). Innovation and Incentives: Evidence from Corporate R&D. The Review of

- Economics and Statistics, November 2007, 89(4): 634–644

- Curran, B., & Walsworth, S. (2014). Can you pay employees to innovate? Evidence from the Canadian private sector. Human Resources Management Journal, 24(3), pp. 290-306.

- Caniëls, M. C., De Stobbeleir, K., & De Clippeleer, I. (2014). The Antecedents of Creativity Revisited: A Process Perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2).

- Teresa M. Amabile (2013).

- Componential Theory of Creativity. Encyclopaedia of Management Theory (Eric H. Kessler, Ed.), Sage Publications, 2013.

- C. Andriopoulos (2001). Determinants of Organisational Creativity: A Literature Review8 Martin Dewhurst (2009). Motivating people: Getting beyond money. McKinsey & Company. https://

- www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/motivating-people-getting-beyond-money#.

- F. Fontana, C. D’Alise, M. A. Marzano 2015). Incentives and Innovative Propensity. American Research Institute for Policy Development.

- Martin Dewhurst, Matthew Guthridge, and Elizabeth Mohr (2009). Motivating people: Getting beyond money.

Leave a Reply