What’s different between Apple and your local market? What does it take for an organisation to be “innovative”? Is money the only factor causing innovation in a company?

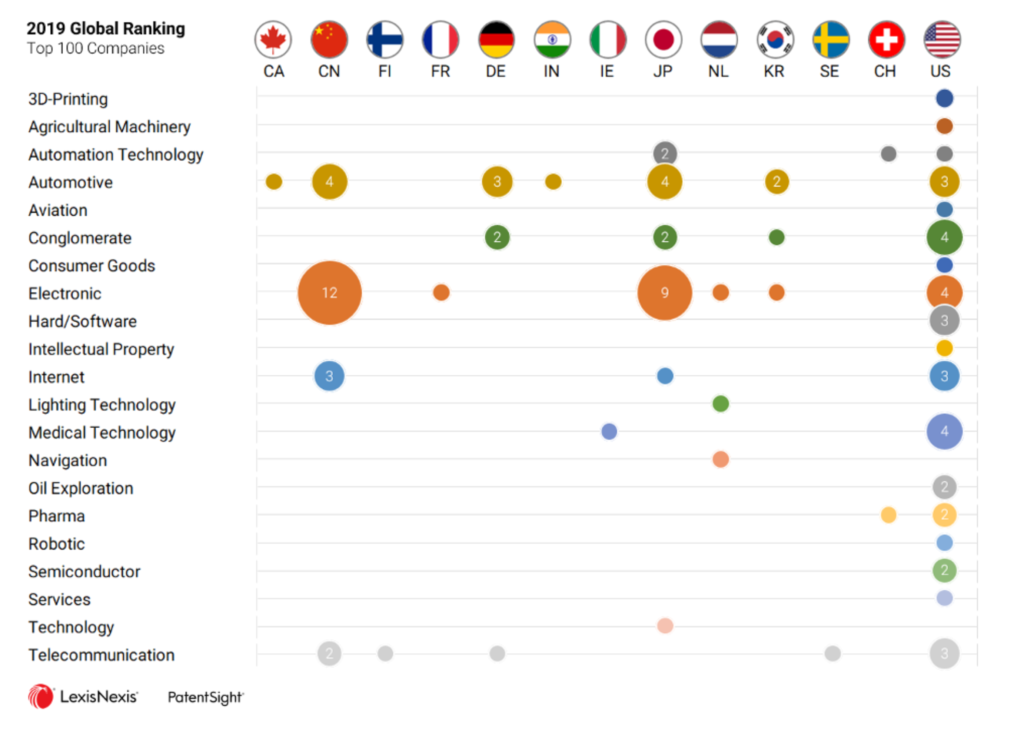

In 2019, according to the PatentSight Innovation Ranking, 38 of the most innovative companies in the US are based in the US, 21 in China and 15 in Europe. With China and Japan, Asia leads the innovation in the electronics field, while US companies lead in medical technology patent innovation.

Focusing on the US, among the top 10, you can find tech companies like Alphabet, Qualcomm, Intel, Microsoft, Honeywell, Apple, and GE, while Johnson & Johnson is leading the chart by innovating in the medical technology field, with a patent portfolio focused on biosensors and surgical robotics, mainly created by some of the 300 companies acquired by the medical “colossus”.

In front of those data, one may wonder, “What is behind those innovation capacities? Why some firms are better than the others in extracting innovation from their R&D departments?” This essay will discuss whether incentive paid to employees accounts for the most massive part of the difference between R&D capacities within firms, or whether there is something “more”.

Grounding

Starting the research, it becomes fundamental to define the limits and the scope of the term “incentive pay”. Since the study’s objective is to analyse how different company incentives scheme may affect the R&D activities, it is evident that any incentive policy needs to be funded. Thus incentive pay is defined as any company cash outflow paid directly to the employees, through a direct transfer of cash or stock options, or indirectly, through the concession of a benefit, such as a free day.

It is important to remember also the definition of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: intrinsic motivation is the drive to engage in some activity because it is exciting and involving, while extrinsic motivation is defined as any motivation that arises from sources outside of the task itself. It essentially matches with the incentive pay described above.

Starting from here, it is possible to investigate the efficacy of incentive pay, and one of the first steps before diving into the literature is to look up whether any theoretical explanation exists.

A Theoretical Point of View

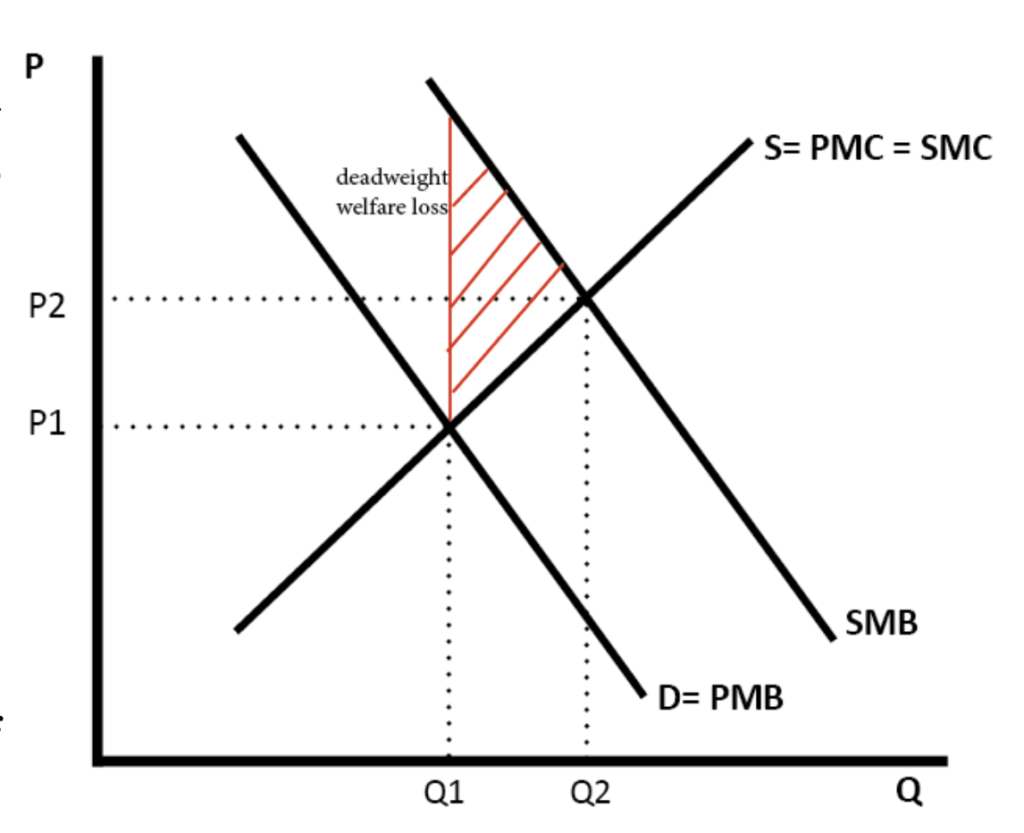

Innovation could be defined as a positive externality that benefits a third party when a specific good is consumed or produced. A farmer who grows apple trees benefits a beekeeper because the beekeeper gets a good source of nectar to help earn more. With positive externalities, the marginal social benefit is greater than the “private one,” thus, the price needs to be modified until a social optimum is reached.

Extending the concept, the producer of knowledge is creating a positive benefit for the rest of the firm’s population or the sector, thus (s)he should be rewarded directly to keep the production of knowledge optimal.

As it will be presented afterward in this report, one of the biggest argument against the efficacy of direct remuneration to inventors and innovators is that money is not always effective as an incentive: it is sometimes defined as a hygiene factor, an element whose fulfillment relieve peoples’ pain but do not makes them happier once dissatisfaction disappears. Recalling Maslow’s theory, You can portray human needs in the shape of a pyramid with the most significant, most fundamental needs at the bottom and the need for self-actualisation and transcendence at the top. Individuals’ most basic needs must be met before they become motivated to achieve higher level needs, while counterintuitively, humans tend to look for those on the top. Linking that to innovation incentive, it could be argued for sure that, despite playing a role as a hygienic factor, money help humans achieve a considerable amount of elements present in Maslow’s pyramid.

Having found theoretical evidence, it is possible to start looking for an empirical one.

The First Piece of Evidence

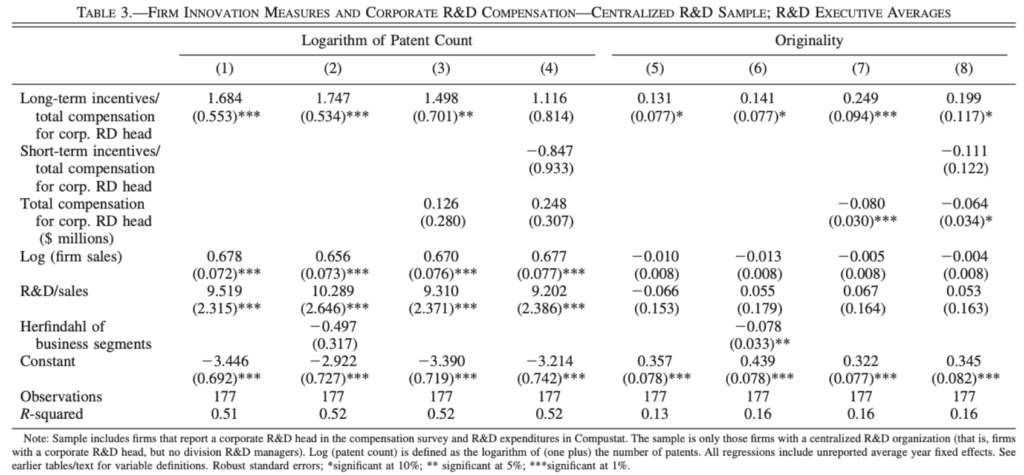

In the late 1980s, compensation of central research personnel began to be linked to the economic objectives of the corporation. In this context, Joseph Lerner and Julie Wulf tried to investigate whether the shift of compensation to R&D corporation heads have caused more patent awards, more cited patents and patents of more extraordinary originality. To do so, the paper of the two authors has examined how the compensation practices have shifted to a heavier utilisation of long term incentives such as restricted stock and stock options and how this shift had granted better results in terms of creative output.

Few disclaimers are necessary to weigh the results:

- There is little association between long-term incentives for corporate R&D heads and innovation in firms with decentralised organisations: corporate R&D heads in centralised organisations have more significant influence over R&D decisions relative to those in decentralised organisations.

- It is not possible to distinguish whether performance pay is coming from better decisions about project funding or from selection effects of attracting more innovative R&D managers that foster innovation because the data are not sufficient to distinguish the two products; more research may be needed.

- The period examined is characterised by a noticeable flux, while data coming from a period of equilibrium where supply and demand of incentives stabilise at an optimal level would be more reliable.

As mentioned before in the research, two datasets are utilised: one about compensation and innovation. The compensation dataset comprises an unbalanced cross-industry panel of more than 300 publicly traded US firms over the years 1987 to 1998. That has a rich array of compensation data for senior and middle corporate management. More than 75% of the firms in the data set are listed as Fortune 500 firms in at least one year, and more than 85% are listed as Fortune 1000 firms. The survey data for firms reporting a corporate R&D head are linked to patent data from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

The relationship between citations and compensation of the corporate R&D managers with R&D organization is reported in the table above. To consider the delay between reward pay and patent registration, a lag of two years is employed in analysis so that patents awarded in 1995 are related to compensations in 1993. Firm citations are initially regressed on the ratio of long-term incentives to total compensation for the corporate R&D head and find that the coefficient is positive and both statistically and economically significant. It is possible to notice from columns 2 and 3 also that business level of focus and concentration is positively correlated with heavily cited patents. From column 4 and 6, it is possible to grasp the idea that the real difference is made by long-term incentives: the short-term incentive ratio and total compensation are not statistically significant, and it is one of the enormous acknowledgement of the research.

In the following table, two additional measures are introduced: patent awards and patents’ originality (measured with coefficients varying from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 1), then the analysis is repeated for each of them, and also the results look similar, except for the long term incentive in column 4 that stops being significant.

All in all, long-term incentives for the corporate R&D head are associated with more heavily cited patents, more original patents, and more patent awards, while short-term incentives are not equally effective.

But this is not the only piece of evidence we have, and you can check how it goes in part 2. How do you think it will continue?

I wanna thank Chiara and Riccardo, that run the research with me during university.

Cited in this article:

- Innovation Ranking 2019. Are you among the most innovative companies in the world? https:// www.patentsight.com/innovationranking

- Abraham Maslow (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review. 1943. Josh Lerner and Julie Wulf (2007). Innovation and Incentives: Evidence from Corporate R&D. The Review of

- Economics and Statistics, November 2007, 89(4): 634–644

- Curran, B., & Walsworth, S. (2014). Can you pay employees to innovate? Evidence from the Canadian private sector. Human Resources Management Journal, 24(3), pp. 290-306.

- Caniëls, M. C., De Stobbeleir, K., & De Clippeleer, I. (2014). The Antecedents of Creativity Revisited: A Process Perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2).

- Teresa M. Amabile (2013).

- Componential Theory of Creativity. Encyclopaedia of Management Theory (Eric H. Kessler, Ed.), Sage Publications, 2013.

- C. Andriopoulos (2001). Determinants of Organisational Creativity: A Literature Review8 Martin Dewhurst (2009). Motivating people: Getting beyond money. McKinsey & Company. https://

- www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/motivating-people-getting-beyond-money#.

- F. Fontana, C. D’Alise, M. A. Marzano 2015). Incentives and Innovative Propensity. American Research Institute for Policy Development.

- Martin Dewhurst, Matthew Guthridge, and Elizabeth Mohr (2009). Motivating people: Getting beyond money.

1 thought on “🤑 Is Money the Best Way to Boost Innovation? – Part 1”